“Zoom University”: Students and Instructors on Pandemic Learning

Written by Michael Ge, WashU senior psychology major, he/him/his

You hear your alarm buzz, and groggily wipe the drowsiness from your eyes. A wince at your phone shows that it’s almost time to start getting ready for your 10:00 AM class. Lugging your reluctant feet out of bed, you engage in the long and arduous routine of preparing for your day of classes.

Flop out of bed. Groan into your chair. Click a few buttons, do the damned 2FA log-in, and congrats. You’re in class.

Welcome back to another day (or night, for those overseas) of pandemic learning– or as some students ambivalently nicknamed it, “Zoom University.”

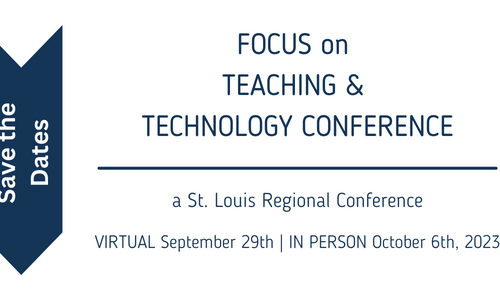

On October 20th, 2021, the Center for Teaching and Learning at WashU ran a panel titled “Student Voices: Reflections on Pandemic Teaching.”

Five undergraduates, yours truly included, were invited to speak directly with around thirty instructors. For one hour, students engaged directly with instructors discussing what we thought about pandemic learning and its impacts on our college experiences. As a dual-ended dialogue, instructors recounted stories and voiced questions about their key concerns with online-only education and in-person instruction’s return. Themes rapidly flooded our conversations. A lack of organic social interactions meant students couldn’t see or make friends, and instructors couldn’t see if lectures were connecting with students. Asynchronous classes struggled to establish clear methods of communication– Canvas, email lists, Slack, and even Discord were all tossed about into the salad mixer of “what the heck is happening.” Some students felt there was a lack of structure. Some instructors felt like they enforced too much structure.

Most of all, across the aisle, online burnout was clear to see. We missed each other. Not wholly in a soppy, emotional, “I will always love you” Whitney Houston way, but in a fundamental way. Regardless of your philosophies about education, our system operates on the active presence of a learner and slightly-more-knowledgeable learner (also sometimes called a teacher). This relationship, of students and instructors, felt defeated by Zoom at times. How do I connect with my instructor and learn from them if I can’t stand another second of staring at a screen? How do I connect with my students and teach them if they won’t even bother turning their cameras on? What if breakout rooms were more harmful than useful for the learning experience?

Countless cons from Zoom University found their mark amongst students and instructors, all nodding their heads in affirmation of each other during the panel. Yet when the moment came to synthesize our thoughts, deliver our seemingly-assured condemnation of Zoom University, and go home happy with our confident opinions… we paused.

Our consensus about pandemic learning was unclear.

===

Several hot topics drove our decisive indecision. Each topic is roughly broken into student panelists’ and instructors’ thoughts, with my own on the matter sprinkled in. Remember that five undergrads cannot speak for the whole student body, thirty instructors cannot speak for all their colleagues, and I can only speak for myself. Lastly, this list is non-inclusive. Every student and instructor could probably write a book about their experience– I’ve selectively chosen two that seemed most relevant for both groups.

Looking for a chance to speak, ask, and learn from the other side of the aisle? The CTL believes learners and instructors should be willing to ask each other questions aside from course material. If you do too, contact Sally Wu at sallywu@wustl.edu with your ideas, questions, or interests in these efforts.

1: Social Interactions in Class

Learning is a connection between student and instructor. College is a connection between teenagedom and young adulthood. What if these connections sever?

Students

Burnout. Burnout burnout burnout. Google N-Gram, a search engine that parses through and charts word frequency through written literature, shows an all-time peak of the word “burnout” in 2019.*** Memes about burnout flourished on student’s despair. A toxic irony reared its ugly head during COVID: students pre-COVID may have dreaded walking to an 8:00 AM, but no one ever wanted mandatory house confinement as a solution to their problems.

First years notably took the hardest hit. Panelists, who ranged from second-years to fourth-years, noted that older students entered pandemic learning with *some* connections made organically– sitting next to people in class, awkwardly bumping into a classmate in line for a 2 AM half and half, getting involved with student organizations– fared slightly better socially than younger students. A paper by Nature corroborates the panel’s general thoughts that acute social isolation resulted in a sense of social starvation— starvation similar to being deprived of regular food-food.

Instructors

How do I get my students involved if they are tired? If they won’t even turn their cameras on? If it turns out that something has happened to my student, how should I care for them and their growth? In fact, if I need to care for my own family, how do I reconcile accommodating my students and my loved ones?

Our panel didn’t find an answer to these questions that were already present for teachers and exacerbated by COVID. Both students and instructors reflected that an increase in emotional acumen– an instructor’s adaptability, sympathy, and empathy– was beneficial across the aisle. Yet with this acumen came a tension: more flexibility often led to increased time commitment by instructors. Similarly, for students, the work-life balance seemed at risk of rupturing upon every extension-request email, each ask for an out-of-office-hours meeting, and countless hours figuring out how the hell break-out rooms work outside of class.

The Good Part

Online-only engagement forced instructors to innovate, finding new ways to engage students while online. Tools such as Poll Everywhere, dedicated question boards like Piazza, and class chats with Slack were all mentioned as proof that, if need be, some parts of organic in-class discussion can be powerfully supported with asynchronous tools.

Note that I say “some parts.” Do I prefer using Slack as my only form of communication while trying to make friends in a 300-person psychology class again? No. But does having a consistent line of communication with my class at large and the instructors that I can use anytime make for a great optional resource? Yes, yes, yes.

Students also shared that an instructor’s honesty during COVID was incredibly humanizing and worked against a sense of social deprivation amongst students. The logic for this student claim, for me, follows this: I assume most graduate and doctoral degrees that instructors at WashU hold probably don’t cover managing the stressors of a global pandemic (much less while teaching!). As such, hearing my instructor state that the occasional drop-off in energy is due to virtual burnout, or that Zoom is frustrating, or that they’re trying their hardest adapting to an entirely-online structure makes sense. The five students in the panel actively knew instructors were trying their best. Thus, we panelists preferred instructors that communicated and gave what they can to learners while maintaining their own sanity as important to people other than students.

2: Online Engagement: Lectures and Canvas

Students

Especially when online platforms became the only way to disseminate rubrics, assignment sheets, and any other course materials, students rapidly made the rough correlation that instructors with disorganized Canvas pages were uncaring for their student’s learning experience. This is a correlation, not a statement of fact. A disorganized Canvas page does, however, not make a great first impression on students. Learners enjoy being able to find their syllabi under the syllabus tab and find their weekly readings under the right week. Think grocery shopping. If you saw an aisle sign that says “Cookies,” walked in, and found yourself perusing paper towels, wouldn’t that be confusing?

There were a bunch of smaller topics that came lumped with switching over to an online-only course platform. Online textbooks were nice– unlike their physical counterparts, they are much lighter (and often cheaper!). Yet, these textbooks or online reading platforms could be prone to technical errors or reliant on internet connection. Another topic is how course materials and lectures were organized. Rather than managing physical folders full of assignment sheets, lab reports, or writing assignments, students could now use a well-designed Canvas course as their scaffolding. A fine example is using modules to clump related items of weekly topics, creating a temporal structure that students can navigate through. Some instructors would even directly link relevant lecture material to certain modules to illustrate the connection between lecture material and assessments at hand.

On the topic of lectures, but more specifically for asynchronous-based classes, panelists mentioned the ability to rewind and pause their lectures started as a blessing and ended as a double-edged sword. Panelists felt the urge to encode everything upon their first watch of a lecture, greatly increasing the amount of time taken to watch a lecture.

Instructors

I have spoken with plenty of instructors saying that setting up a great Canvas page is tough– that the editing tool is finicky-at-best, and that students always seem to find things in the end. Yes, I agree that editing the page can be confusing (I got my own Canvas course to play around with and instantly got submerged by layers of complexity). Yes, students seem to find what they need.

Not only is Canvas hard to use, but the plethora of additional tools and integrations also represented a deluge of information that instructors had to work with. The use of electronic methods for assignment submission work most of the time, but there are still out-lying cases where a document cannot open properly, and file transfer through an integration fails, or some other fringe tech error occurs. On top of dealing with third party integrations, Zoom lectures became a whole new beast to tame. Small discussion-based classes may have been able to just open a room and launch into a conversation, but large lecture-based classes often had to manage breakout rooms, address how students could best ask questions during lecture, and find ways to generate participation if need be.

The Good Part

Zoom University came with a free-of-charge three credit course that everyone had to take: how to navigate Canvas. Syllabi were encouraged to actually be put in the syllabus tab. Modules were guided by weekly progression rather than by random, and all of our paper assignment sheets, textbooks, and feedback went into the screen. This organization streamlines the process of finding course materials and makes Canvas as a valuable hub of learning materials even if the class meets in-person. Instructors’ use of Canvas shifted from around 40% to over 90% during the pandemic, and remains near 90% this semester even as most classes shifted to in-person instruction.

The access to lectures, rubrics, online texts, and more has expanded our understanding of what is possible with online education. Students and instructors do not have to wait until class time to discuss assignments, ask questions, and engage with content. This shift gives more agency to students on how, when, and where they move through materials.

===

Again, is all of this resoundingly good? No. Zero people on the panel said that they felt fulfilled when every single aspect of education became transmitted solely through a screen. But was there benefits to bringing aspects of traditional, in-person education online? Undoubtedly, resoundingly, yes.

***The Google N-Gram search engine is not meant as sufficient evidence for the prevalence of burn-out. The search merely offers a easily digestible way to demonstrate *one* aspect of burnout’s recent prevalence.